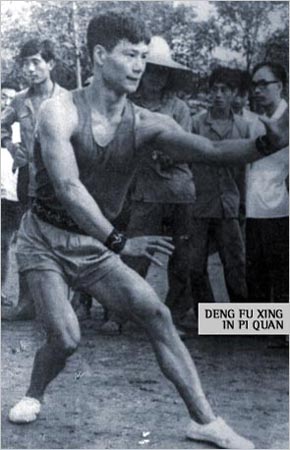

In my last column I introduced the triangular stance and the footwork for splitting. In this installment I will concentrate solely on the hand movements of splitting. First, it helps to have a firm image of the trajectory of the striking hand. Splitting derives its name from the extended arc, which the striking hand describes, likened to the arc, which the business end of an axe traces when chopping wood. It is this image that the Chinese had in mind when splitting was equated to metal in the five elements cosmology. Classic texts on Xingyi describe the force of splitting as "pi chai," or splitting wood. We will not delve further into how to develop and applying power of splitting in this issue, as it is difficult enough to get the movement correct without concerning ourselves with more advanced problems.

All movements in Xingyi contain components of other elements, and splitting is no exception. As we saw in the first article of this series, pure splitting is up and down motion only. Unless our target is directly beneath our striking hand, this presents a problem of delivery. Forward motion is supplied by drilling, orzuanquan, which bridges the gap between us and the opponent. If contact is made with the drilling arm, the drilling action allows your arm to slide over the opponent's. Either hand may then follow with splitting or drill and split along the same line. In Xingyi "one hand opens the road, the other follows," meaning that when an opening is created, either by blocking, striking, or slipping in, the other hand can then follow up along the same line.

The

drill-split action shown below is the central tool of Xingyi, much as the

single palm change is the central movement of Bagua. Begin with both hands

in fists, palm up, positioned on either side of your navel. Drive your right

fist up your midline. Your fist should twist clockwise (analog, not digital),

as if turning a screwdriver (the tool, not the drink). When your fist reaches

the center of your sternum, it should move away from you at about 45 degrees,

so that your hand moves in an arc. As your right hand moves upward, bring

your left fist, palm up, to your right elbow, moving along with your right

arm. When your right fist reaches the point where it is in line with your

eyebrows, drive your left fist up the inside of your right forearm. As your

fists meet, open your hands, and begin to rotate them palm down. Strike

forward and down with your left palm as you draw your right palm towards

your belly. After the striking, close your left hand one finger at a time,

beginning with your little finger, make a fist, and rotate it counter clockwise,

until the little finger points skyward. Bring your right fist to your left

elbow. Drive it up your left forearm, and execute the same series of motions

above, only striking with the right palm, withdrawing the left. Repeat several

hundred times a day until it becomes a reflex.

The

drill-split action shown below is the central tool of Xingyi, much as the

single palm change is the central movement of Bagua. Begin with both hands

in fists, palm up, positioned on either side of your navel. Drive your right

fist up your midline. Your fist should twist clockwise (analog, not digital),

as if turning a screwdriver (the tool, not the drink). When your fist reaches

the center of your sternum, it should move away from you at about 45 degrees,

so that your hand moves in an arc. As your right hand moves upward, bring

your left fist, palm up, to your right elbow, moving along with your right

arm. When your right fist reaches the point where it is in line with your

eyebrows, drive your left fist up the inside of your right forearm. As your

fists meet, open your hands, and begin to rotate them palm down. Strike

forward and down with your left palm as you draw your right palm towards

your belly. After the striking, close your left hand one finger at a time,

beginning with your little finger, make a fist, and rotate it counter clockwise,

until the little finger points skyward. Bring your right fist to your left

elbow. Drive it up your left forearm, and execute the same series of motions

above, only striking with the right palm, withdrawing the left. Repeat several

hundred times a day until it becomes a reflex.